Ever since I commenced my training as a Speech-Language Pathologist

back in the late 1970s, I’ve been aware of the problematic nature of the

profession’s chosen name. In fact, back at that time, in Australia, we used the

title Speech Pathologist, and in the UK, it was Speech Therapist (a term that

prevailed here for many years too). In recent decades, both Australia and the

UK have followed the lead of the USA, by inserting the word “language” in our

profession’s title, leaving us with Speech Language Pathologist in countries

such as Australia, the USA, and Canada, and Speech-Language Therapist (or

Speech and Language Therapist) in the UK and New Zealand. I think this helps, but we still have some

explaining to do, as “speech” tells such a limited part of the story regarding

our scope of practice. I’m going to focus here on language and literacy, but

bear in mind that Speech Language Pathologists (SLPs) also work in areas of

voice, fluency, hearing, acquired neurological disorders such as aphasia (e.g. after stroke),

cranio-facial disorders (such as cleft palate), and dysphagia (swallowing disorders), to name a few.

Let’s start by looking at the basic difference between speech

and language. When SLPs describe speech, they are referring to the mechanical processes involved in breaking up an

outgoing air-stream in order to produce recognisable sounds. We break up the

air stream in some cases by momentarily stopping it altogether e.g. in the case

of the sound/p/, where the lips coming together and then apart, produces a tiny

“explosion” of air, meaning that /p/ is referred to by linguists as a “plosive”.

Some speech sounds are produced with voice (vibration of the vocal cords), such

as /d/, /g/, /b/, while others are produced in the same way in every respect

except there is no voice used: /t/, /k/, and /p/. The branch of linguistics that

is concerned with speech sounds is phonology.

It’s important to note that phonology is part of the language

system, so the convenient and everyday distinction that SLPs commonly make

between speech and language is somewhat arbitrary and does not always play out

well in clinical practice, where children have mixed disorders across different aspects of language.

Mastering the phonology (speech sound system) of the language

or languages to which one is exposed in the early years of life is no mean

feat. Most of us are familiar with the experience of interacting with chatty toddlers

who are hard to understand, so we find ourselves deferring to one of the

parents to “interpret” for us. By three to four years of age, however, most

children can make themselves understood most of the time, even if imperfectly,

and with many persisting errors, e.g., reducing consonant clusters to one

consonant, to say “dop” instead of “stop” (in this case, the effect of co-articulation means that voicing has also been introduced). By school entry, most

children are not only talking in full sentences, but can make themselves

understood without a parent “interpreter”, though they may still have

difficulty with /s/, /r/, /l/ and ‘th’ sounds: Ɵ (voiceless) and ð (voiced). Some children, however, display speech sound disorders (SSDs,) and their

speech is difficult even for familiar communication partners to understand, relative to that of their age peers.

The importance of SSDs in the school context goes beyond children's ability to make themselves understood. As Pennington and Bishop noted in 2009, “….individuals with

SSD often show deficits on a range of phonological tasks, including speech

perception, phoneme awareness, and phonological memory”. These skills are all

deeply connected to the processes involved in decoding and making sense of

print, so it is not surprising that having a SSD in the early school years

creates a significant risk for difficulties learning how to read, write, and spell.

This might go some of the way towards explaining why, when children are

referred by classroom teachers to SLPs for assessments, based on concerns about

their speech, that the SLP may wish

to discuss with the teacher, the implications of the child’s overall speech and language profile

for being able to succeed in reading and writing.

If you are interested in finding out more about speech sounds,

their typical development and their

disorders, you can’t go past this site, written by my friend and colleague, Dr

Caroline Bowen, AM.

Language refers to

a complex set of skills that in addition to phonology, includes vocabulary,

syntax (rules by which we link words together to form phrases and sentences),

morphology (base words and affixes that change their meaning), and pragmatics

(the ability to make socially and contextually appropriate adjustments to

communication style in a range of real-world contexts, and to “read the play”

in the interactive space). Language development is closely related to the development of cognition (e.g., attention, planning, self-monitoring), memory (working, short and long-term), emotional self-regulation, and the development of empathy and social cognition.

However, language skills in humans are something of a paradox. Language

is our evolutionary advantage over our nearest primate relatives, setting us

apart on planet earth from all other species. That’s not to say that other

species don’t have communication abilities; they clearly do. But humans have

been particularly blessed in this respect, with a capacity that unfolds from birth

(some would say even earlier) and develops apace in the pre-school years and

well beyond.

While oral language skills are biologically natural, they are no set-and-forget function, as I have written about previously as they are sensitive to environmental exposure and the quality of the

interpersonal spaces that children experience in the early years. Written language,

on the other hand, is a social contrivance – something we humans have invented

for social, economic, intellectual, and cultural benefits, but it is not natural

and has to be learned. Some fortunate children acquire the nuances of the

written code relatively seamlessly, while others do not, and will only succeed

with explicit instruction, and possibly additional therapeutic support. These children do not necessarily have a diagnosable "disorder" and nor are they always easy for teachers to identify in the classroom context.

Speech Language Pathology expertise spans all forms of human communication: spoken, gestural,

augmentative, and written. Reading and writing are forms of communication, so

they are within our scope of practice. The other factor that places reading,

writing, and spelling fairly and squarely in our scope of practice is that

these are all fundamentally linguistic

activities, and language is our thing, whether we are thinking about typical

development, or development that is impacted by one or more neurodevelopmental

disorders. The linguistic basis of learning how to read is strongly represented

in the Simple View of Reading, which holds that reading

comprehension is, in mathematical terms, the product (not the sum) of a child’s ability to decode an unfamiliar

word and her ability to understand what the word means. So,

decoding skills (mapping phonemes onto graphemes) are essential and

non-negotiable, as are language comprehension skills.

Practically all neurodevelopmental

disorders (for example, autism spectrum disorders, intellectual disability,

attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder) have implications for speech and language

development. This can also be the case for brain injury sustained in early life

(e.g., due to infections such as meningitis or encephalitis; hypoxia, as in

near-drownings; trauma due to falls or assaults). Other disorders present at

birth or in early life that can impact speech and language development include

hearing loss and cerebral palsy. And of course, there is a significant number

of children who have a developmental language disorder without necessarily displaying any of these conditions.

Finally, we know that early maltreatment(abuse and/or neglect) will impact on a child’s communication milestones,

across speech, language, and social skills.

We know that there is significant overlap between the

existence of language and reading disorders, and that sometimes, children’s

language skills are only called into question at the point at which they

struggle with the transition to literacy.

“…poor comprehenders do not have a comprehension impairment

that is specific to reading. Rather, their difficulties with reading

comprehension need to be seen in the context of difficulties with language

comprehension more generally.” She goes on to state that “….dyslexic children perform poorly on oral

language tasks that involve phonological processing, such as phonological

awareness, nonword repetition, rapid naming, name retrieval and verbal

short-term memory”.

None of this means, of course, that language and other aspects

of communication are not shared turf with other professionals. It is in everybody’s

interests for teachers, psychologists, and occupational therapists, among

others, to have at least a good working knowledge of language and how it works. Naturally, this

will be variable, in the same way that SLPs’ knowledge of psychometric

testing, or their knowledge of curriculum will be variable.

In order to be able to assess and treat children with reading

and writing difficulties, SLPs must first understand the typical ways in which

such skills are acquired, and major approaches to their instruction in the

early years of school. For this reason, literacy forms an increasing component

of SLP university degrees, and SLPs exit their training equipped with at least

the basics of theoretical frameworks such as the Simple View of Reading, the

importance of phonological and phonemic awareness, optimal ways of

transitioning children from oral language foundations to print, via a range of

media, and effective forms of early intervention for children who are

identified as struggling.

Strong receptive and expressive oral language skills are the

secret weapon of some children when they arrive at school. In and of themselves,

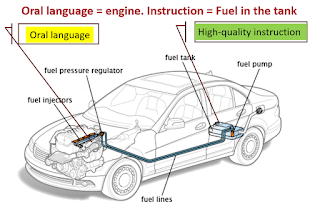

they are not enough to get children across the bridge to literacy, but they are a vital start. One way of thinking about this relationship is that oral language skills are the metaphorical car

engine and excellent classroom instruction (and additional support if needed) is the fuel

in the tank.

Some children have engines (oral language skills) that need to be made more powerful in order to improve their readiness for the transition to literacy. If that's the case, then schools need to rise to this challenge, as it is the job of schools, not parents, to teach children how to read. All children benefit from the fuel of high-quality instruction provided by highly knowledgeable teachers. I have blogged previously about the fact that many university education programs have unfortunately discarded the vital knowledge about language and how it works, that teachers need to have at their disposal. It is pleasing, therefore, that in many schools, teachers and SLPs work collaboratively, pooling their knowledge of language and curriculum in order to ensure optimal mainstream reading instruction, as well as small-group, or even individual support to students who are struggling. Some practitioners hold dual qualifications in both Speech Language Pathology and Teaching and they are particular assets in the school setting.

Speech Pathology Australia has produced a guidelines document for SLPs working in the area of literacy, which is available as a members-only download.

The American Speech and Hearing Association (ASHA) also has a Position Statement on Roles and Responsibilities of Speech-Language Pathologists with Respect to Reading and Writing in Children and Adolescents.

You might also find this free, open-access guide useful: Reading problems and what to do about them, produced by Australian SLP, David Kinnane.

This open-access paper was published in August 2020: The Science of Language and Reading.

So, in keeping with the title of an open-access

paper of mine from 2015, SLPs work in the area of literacy because Language is Literacy is Language.

Great post.

ReplyDeleteenetget.com

This comment has been removed by a blog administrator.

ReplyDelete