As the world continues, 18 months on, to battle its way through the enormous challenges thrown up by COVID-19, we’ve all had to come to grips with the uncomfortable reality that our talented, knowledgeable and hard-working scientists don’t have an immediate, ready-made answer that also happens to be incontrovertibly right, for every question we ask.

We have had an opportunity, however, to look at what happens, when different nations approach the same problem in different ways. And we’ve been able to observe in real time how these responses play out against contextual factors such as poverty, density of living conditions, population demographics, and the level of advancement in different health care systems.

One of the most hotly contested aspects of the COVID-19 debate, from the earliest stages, was the merits, or otherwise of requiring people to wear masks in public. Professor Trisha Greenhalgh of the University of Oxford has been both a staunch advocate of masks as well as clear science communicator about why we have to act in the absence of “robust empirical evidence” that unequivocally supports their use. You can read a long, but clear thread about her reasoning and research at this link.

In Tweet No. 11 of the above thread, Professor Greenhalgh states: The most fundamental error made in the West was to frame the debate around the wrong question (“do we have definitive evidence that masks work?”). We should have been debating “what should we do in a rapidly-escalating pandemic, given the empirical uncertainty?”.

Professor Greenhalgh goes on to outline why, in this situation, turning to the gold-standard randomised controlled trial (RCT) is not the right response, which may seem like surprising advice from an esteemed public health professor at the University of Oxford. She explains (among other things) that well-controlled RCTs that rely on statistical significance, are likely to miss reductions in spread that make a real-world, practical difference.

Tweets 25 and 26 in thread state:

Take the number 1 and double it and keep going. 1 becomes 2, then 4, etc. After 10 doubles, you get 512. After 10 more doubles, you get 262144. Now instead of doubling, multiply by 1.9 instead of 2 (a tiny reduction in growth rate). After 20 cycles, the total is only 104127.

=> if masks reduce transmission by a TINY bit (too tiny to be statistically significant in a short RCT), population benefits are still HUGE. UK Covid-19 rates are doubling every 9 days. If they increased by 1.9 every 9 days, after 180 days cases would be down by 60%.

So – what does this analysis on mask-wearing have to do with reading instruction?

Like many others dedicated to the imperative of better reading outcomes for all children, I understand that reading experts are often in the same boat as public health experts. We have to offer well-considered advice in the absence of all of the empirical evidence that we would like to have available.

In both public health and reading research, the evidence may be unavailable because the relevant studies have not been done. In other cases, there are studies, but they are judged as insufficiently powered to provide what is regarded as a “definitive answer” (inasmuch as anything is ever “definitive" in scientific research). This does not mean that we are operating in a complete vacuum however, as there are some widely (no, not universally) agreed state-of-play maxims about the nature of the reading process and the skills that novices need to master to be off to a successful start. I have blogged previously about these on this site.

Like our colleagues in public health, we also need to observe the maxim of “first do no harm”, to minimise the risk that those following our advice inadvertently worsen rather than improve the futures of children learning to read in their classrooms. Not issuing advice can in itself be a form of harm, however, as it tacitly condones a status quo that puts children’s outcomes on a static or downward trajectory.

Failing to take an educated punt on the best available evidence creates the kind of change paralysis that sustains entrenched practices for which the evidence may be virtually non-existent e.g., the use of so-called Three Cueing (Multi-Cueing) and predictable (or leveled) texts, taught alongside banks of so-called “sight words” to be rote-learned by students. Those of us who are privileged to have strong literacy skills simply opting to live with uncertainty and throwing our hands up in the air with an “oh well” resignation, is not, in my view, an acceptable option when children’s lives are literally at stake.

If we apply Professor Greenhalgh’s number doubling exercise outlined above, it’s not difficult to see how, by the end of three years of formal reading instruction, Western industrialised nations have created so many struggling readers. The learning support resources needed to successfully intervene for struggling readers are akin to the intensive care units and respirators needed to treat people unnecessarily infected with COVID-19. They are expensive and difficult to resource from a human labour-force perspective, and sadly, they do not always work. Like COVID-19, the burden of poor outcomes in classroom reading instruction is disproportionately borne by those who are already disadvantaged in some way.

To paraphrase Professor Greenhalgh’s analysis of the effectiveness of masks, I would suggest we have been asking the wrong question in early reading instruction with respect to decodable texts* (Do we have definitive evidence that decodable texts “work”?) and should ask instead: What should we do in the context of widespread poor reading data in English-speaking countries, given the empirical uncertainty?

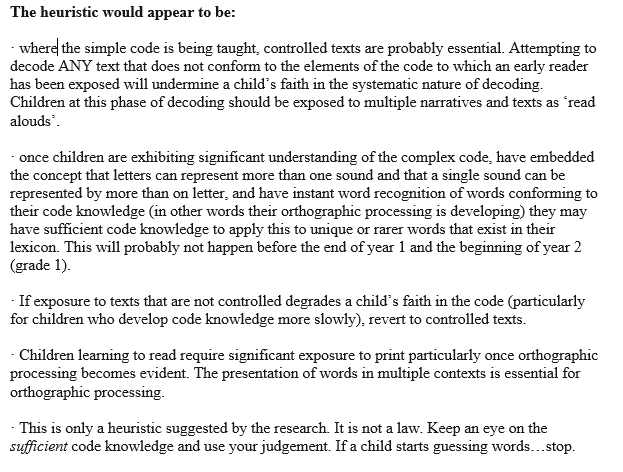

In the absence of a clear, empirically-derived answer, I can think of no better evidence-and-practice-informed, classroom-friendly advice and guidance than that provided on The Reading Ape blog in what seems to be an undated post (reproduced with permission):

Like masks, decodable texts are not a stand-alone “solution” to a population-level problem. Their impact is also difficult to study in isolation from other interventions (e.g., structured and explicit code teaching delivered by knowledgeable educators, using a clear scope and sequence). But if we were asked to place the available practices in a rank order, my Number One vote would be for explicit teaching of how the English writing system works (for both reading and spelling), accompanied by opportunities for practice to support early mastery of automatic decoding, via carefully selected decodable texts**.

Of course, decodable texts do not represent the full range of morpho-phonemic, syntactic and semantic complexity of the English language. But why should they? We are talking about novices here. Texts of that sophistication are not those we ask 5-and 6-year-old children to read, in the same way that we do not ask beginning pianists at the outset to play pieces that contain all the notes in a chromatic scale (let alone all of the complex rhythmic patterns that exist in the complete musical repertoire).

The COVID-19 pandemic will no doubt teach us many things, including the importance of making weighty decisions in the face of uncertainty and ambiguity. Professor Greenhalgh backed masks from the outset, applying a mix of scientifically-derived principles and dare I even mention it, common sense.We need to do the same on the use of decodable texts, as part of an explicit approach to teaching the code. Using decodable texts in isolation from other rigorous practices would be like advocating mask use, but not reducing social mobility, rolling out vaccines, and encouraging physical distancing.

My prediction? History will view masks and decodable texts in similarly positive lights at a population level, and 2021 detractors and naysayers will be re-writing their positions to be on the right side of said history.

COVID-19 achieved pandemic status in early 2020, but low literacy levels have been endemic in English-speaking industrialised nations for decades. If we are waiting for the perfect RCT to illuminate the path, then we may as well pray for a vaccine against poor reading outcomes. Oh wait……we may already have one, albeit one with imperfect efficacy and a continued need for vigilance. I refer of course, to widespread application of practices we already have to hand, that promote (I did say not say guarantee) better outcomes at a population level and reduce the burden borne by those who are already socially and economically disadvantaged.

*****

Information about recommended sets of decodable readers can be obtained on the DSF website and also on Alison Clarke's Spelfabet website.

*A reader, Berys, has commented (below) that the term "controlled" text is preferable to "decodable" text and I agree with her on this and for the reasons she outlines: in theory, all texts are decodable, for those who know how the code works, but what we are really referring to here is texts that control the text complexity, in a graduated way, to ease novices into the process of reading connected text. Harriet points out below too, that we should be thinking about multiple criteria, not just decodability (e.g. word frequency and literary quality). Both are relevant and important points. Thanks Berys and Harriet! 🙂

** It should go without saying, but I will say it anyway: decodable texts should never be the only books that children are exposed to and once children have mastered the code to automaticity as judged by a knowledgeable teacher, their use can be discontinued. They may, however, be called upon in higher year levels to support struggling older readers.

© Pamela Snow (2021)

I agree that politicians often need to make important decisions when data are unclear. But it is the duty of scientists to be clear about the strength of the evidence, and not claim that the science strongly supports X when in fact the evidence is weak (or in fact highly contested). Is there any study you can cite that provides evidence for decodables? If not, and your conclusion is based on your view that the evidence strongly supports phonics, then you should say that the science supports phonics, and that you think a reasonable conclusion from this is decodable texts are useful. Not say that the science supports decodable texts.

ReplyDeleteFor anyone who has seen me post before, you will know that I think the evidence for phonics is very weak. For instance, there is no evidence that over a decade of legally mandated systematic synthetic phonics in England has improved reading outcomes despite improvements on the Phonics Screening Check itself (showing that indeed phonics is being implemented effectively). For more detail, see: https://jeffbowers.blogs.bristol.ac.uk/blog/buckingham-2020/

Again, I agree that there are political realities that need to be dealt with, and decisions often need to be made on the basis of poor evidence, but this does not provide a license for scientists to engage in spin. I don’t think that should ever be done, but if it is to be done, leave it to the politicians.

Jeff, this is not the place to revisit the ongoing discussion about the effectiveness of phonics, but I recently reread the Fletcher et al. piece (A Commentary on Bowers (2020) and the Role of Phonics Instruction in Reading), and I was struck by its relevance to this discussion of decodables and the importance of integrating skills taught. In particular, when using decodables, we are definitely uniting phonics with meaning (like explaining what 'soy' is when practicing /oy/ and then finding the word 'soy' in the story), and children find it reaffirming to read books that emphasize practice with both a phonics pattern and a vocabulary word as they extract meaning from the stories read to boost comprehension skills. This tension between word recognition and word meaning is something practitioners like me grapple with every day. Here are some pertinent passages from the Fletcher piece about the importance of an integration of skills, how phonology and phonics are taught in the context of meaningful words.

Delete1) Most approaches to reading instruction that include explicit phonics are also focused on meaning and understanding the words and texts used.

2) We believe current reading intervention research generally embraces this complexity, recognizing the value of both explicit phonics instruction integrated with fluency, language, and comprehension practices that reflect the necessary complexity of reading instruction at both the sublexical and lexical levels.

3) At a certain level, however, we must ask how comprehension proceeds in struggling readers if they cannot access the print.

4) Reading instruction should not occur in the absence of opportunities to read and write and oral language development. These opportunities are usually present in reading instruction, making it hard to isolate the effects of systematic phonics instruction. However, these successful integrated approaches rely on facilitating students’ access to word reading and meaning through effective instructional practices that demonstrate the ways in which phonemes map to print in regular and irregular ways providing many opportunities to read words so that the structure of language is acquired both explicitly and implicitly.

5) As Seidenberg (2017) pointed out, many children come to school primed to learn to read. However, because of environmental factors as well as biological factors that make it harder for the brain to mediate reading, many children struggle to learn to decode and therefore are less able to access print. Much of what Bowers (2020) calls exaggeration is a reaction to the need of these children for explicit phonics instruction. Many children do not get the word work they need, partly because it is not intentional, explicit, and well organized.

6) A suitably nuanced and evidenced science of teaching reading is a work in progress. This ambitious enterprise may involve healthy friendly professional disagreement, but it will also need a mindset among all research leaders that acknowledges this complexity over old binary modes of the twentieth century, the importance of this goal to the wide community, and also the importance of communicating it accurately and effectively to all of the users of our science.

Both this piece and Jocelyn Seamer's recent discussion of decodables (Decodable texts - how do we get it right?) make a lot of sense to those of us who work with struggling readers and build our lessons around PA and phonics skills that allow students to read decodable texts featuring the pattern taught and practiced. I am excited about research into 'multi-criteria' texts which have decodability as one criterion. In the meantime, there are decodables out there that are not awful by any means, confirmed by my students who say, 'I love that story'. What they love--in addition to the story elements--is the fact that they can actually read it. Thank you for contextualizing this important subject.

ReplyDeleteThanks Harriet, you make a good point about "multi-criteria" (e.g. frequency and phonetic regularity) texts. To quote Cheatham and Allor (2012) "..the field needs to consider decodability as a text characteristic rather than a type of text".

DeleteAnd I agree, there are many high-quality series of decodable (or as Berys points out below, controlled) texts that have good story lines and are attractive to children - it's possible to address those multiple criteria as well. I linked to some sources for those at the end of the blogpost.

Thanks Pamela, an excellent, educative and entertaining piece as always. One that should be landing in every school inbox in the country. I wonder though, whether there is any chance we can, as the Reading Ape has, make the change from 'decodable texts ' to 'controlled texts'? I know the word 'decodable' has become quite entrenched, but, after all, any text is decodable providing we have the knowledge and skills to read it. "Controlled' or 'phonically controlled' is a much better descriptor.

ReplyDeleteThanks Berys this is an excellent point, which I will take on board in future writing and discussions about this. I've made a slight adjustment above to acknowledge your suggestion.

DeleteBerys suggests using 'controlled' or 'phonically controlled', and I'm wondering if the latter makes more sense in light of the fact that 'controlled vocabulary text' is often used as described by Tim Shanahan in his piece, 'Which Texts for Teaching Reading: Decodable, Predictable, or Controlled Vocabulary?'

Deletehttps://www.readingrockets.org/blogs/shanahan-literacy/which-texts-teaching-reading-decodable-predictable-or-controlled-vocabulary

"Controlled vocabulary readers limit texts to a handful of words that are used repeatedly. New words are added gradually. The major approach to learning these words is memorization. Initially, because they start with so few words, these texts sound very stilted, but as kids memorize more and more words, controlled vocabulary texts sound more and more like language."

Dick and Jane Readers are controlled vocabulary texts.

pg. 1: Dick

pg. 2: Jane

pg. 3: Dick and Jane

pg. 4: Dick and Jane run.

pg. 5: Jane and Dick run.

Pg. 6: Dick runs.

pg. 7: Jane runs.

pg. 8: Run, run, run.

Thanks Harriet - another valuable contribution to this discussion.

Delete